“I always cried before I fight as I’m getting ready to change into somebody I don’t like”: Mike Tyson’s Greatest punch Combination – DOES JAKE PAUL HAVE A CHANCE TO WIN? | HO

Here is a video about Mike Tyson’s left hook to the body followed by Right uppercut.

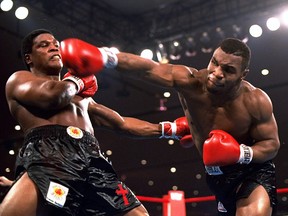

38 years ago today, Mike Tyson connected with a punch so nuclear Trevor Berbick went down three times

On Nov. 22, 1986, a heavyweight boxer barely out of his teens hit a 32-year-old world champion with a punch so destructive that his veteran opponent went down three times from it.

And when Mike Tyson, who had just become the youngest heavyweight champion in the history of boxing with that left hook to the forehead of Trevor Berbick, returned to his corner, he shrugged his shoulders almost sheepishly as if to ask, “Is that all there is?”

Thirty years later, on the anniversary of what looked to be the beginning of an enduring new era in boxing, the same question can be asked about Tyson’s career.

“Thirty years ago? It seems more like a million,” Tyson said in a telephone interview last week. “My whole life has changed since then. I’m a totally different person. I don’t even know that person anymore.”

“That” Tyson had the brashness and invincibility of youth. “I’m the youngest heavyweight champion in history,” Tyson said at the news conference after the bout. “And I’m going to be the oldest.”

Lintao Zhang/Getty Images

This Tyson is a 50-year-old man, saddled with all the insecurities of middle age, worried about his future and unconcerned, he says, with his tumultuous past.

“I have not much faith in life anymore,” he said. “I’m bitter at life. I wasn’t smart enough to be bitter back then.”

Tyson laughed when he said it, but it had the ring of truth.

The Berbick fight, now a hazy memory even for him, turned out to be one of the few real highlights of a volatile and surprisingly brief reign. A little more than three years later, Tyson was an ex-champion, and two years after that, a convicted rapist.

Advertisement 3

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

After three years in prison, he made a comeback and won a version of the title again, but it was a hollow championship, and his career endured disgrace – the biting off of a portion of Evander Holyfield’s ear in 1997 – and ultimately, embarrassment when he quit in his final bout against a ham-and-egger named Kevin McBride in 2005.

Rarely in the history of any sport has a career that began with so much hype and promise ultimately delivered so little. Mike Tyson the phenomenon was real; between 1986 and 1990, the world stopped on the nights he fought.

But Mike Tyson the fighter? In retrospect, the whole added up to less than the sum of its parts.

AP Photo/Jack Smith

Now, the former champion’s boxing career is largely unknown to a new generation raised on computer games, virtual reality and mixed martial arts. To many millennials, Tyson is as remote a figure as Jack Dempsey was to Tyson’s generation. He is better known for bit roles in movies and as the inspiration for a cartoon.

But what a time it was, tumultuous and unpredictable and never boring. So many indelible events crammed into so small a space – Berbick, Michael Spinks, Robin Givens, Buster Douglas, Indianapolis and the amassing and losing of two fortunes, to name just a few – that it is stupefying to realize that by the time he was 21, Tyson’s best days as a fighter were already behind him; his 91-second knockout of Spinks, in what was at the time the most lucrative sporting event in history, came three days before his 22nd birthday.

AFP/Getty Images

Mike Tyson has champion Trevor Berbick going down …

Mike Tyson has champion Trevor Berbick going down …

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty Images

Still, Tyson is the ultimate survivor; of the main players in the ring that night, Berbick is dead, murdered with a steel pipe by his nephew in 2006. So, too, are Tyson’s managers from that time, Jim Jacobs and Bill Cayton, with whom he would have an acrimonious, and in some ways disastrous, split.

Gone, too, is Angelo Dundee, who trained Berbick, and the referee, Mills Lane, has been incapacitated for years by a devastating stroke. Tyson’s trainer, Kevin Rooney – to whom the gesture of bemused surprise was directed – is in the early stages of boxing-induced dementia at 60.

“Me and Kevin, we thought everyone I fought was a bum,” Tyson said. “That’s why I shrugged at him after the fight.”

Asked whether he was nervous before the fight, Tyson said, “Yeah. Nervous I was going to hurt [Berbick] real bad.”

But people close to Tyson painted a different picture, one of a painfully insecure young man beneath the carefully cultivated No Robe, No Socks, No Mercy image.

Steve Lott, who was Tyson’s friend, confidante and all-around factotum – and also his landlord, because Tyson slept on the couch in Lott’s Manhattan apartment – was always cognizant of Tyson’s fragile mental state.

News

‘I’m really embarrassed with myself and my life’: Mike Tyson on Where’s His $400 Million Dollars | HO

‘I’m really embarrassed with myself and my life’: Mike Tyson on Where’s His $400 Million Dollars | HO Tyson became one of the most high-profile and wealthiest sportsman on the planet – but staggering financial mismanagement meant he filed for…

CLINK FLOYD – Mayweather’s 60-day prison hell as he survived on Snickers, paid gangsters for protection, and feared jailer was out to get him | HO

CLINK FLOYD – Mayweather’s 60-day prison hell as he survived on Snickers, paid gangsters for protection, and feared jailer was out to get him | HO FLOYD MAYWEATHER needed to pay for protection and constantly moaned about conditions during his…

OSCAR DE LA HOYA CALLS OUT FLOYD MAYWEATHER Makes $100 Million Offer!!! | HO

OSCAR DE LA HOYA CALLS OUT FLOYD MAYWEATHER Makes $100 Million Offer!!! | HO Oscar De La Hoya is gunning for a fight with one of the greatest boxers of all-time, Floyd Mayweather, telling TMZ Sports he’s got $100 MILLION for Money if he…

Floyd Mayweather REACTS to Ryan Garcia N-Word R₳CIST RANT; Shuts down “NEGATIVITY” to PRAISE Moton | HO

Floyd Mayweather REACTS to Ryan Garcia N-Word RACIST RANT; Shuts down “NEGATIVITY” to PRAISE Moton | HO Ryan Garcia is looking to boxing legend Floyd Mayweather in order to resuscitate his flagging career in the ring — but right now, it is proving…

Smartest move tank has ever made! Floyd Mayweather RESPONDS To Gervonta Davis CALLING HIM OUT To Fight! | HO

Smartest move tank has ever made! Floyd Mayweather RESPONDS To Gervonta Davis CALLING HIM OUT To Fight! | HO The relationship between Floyd Mayweather and Gervonta “Tank” Davis has been a rollercoaster of highs and lows, marked by moments of…

Mike Tyson HD get him a straight jacket put your mother in a straight jacket Lewis press conference | HO

Mike Tyson HD get him a straight jacket put your mother in a straight jacket Lewis press conference | HO “Get him a straitjacket!” That’s how all this craziness started. In 2002, boxing writer Mark ‘Scoop’ Malinowski stood at the…

End of content

No more pages to load